T is for Transport 2

Part two of "L is for Lisbeth"

Lisbeth Frank was born in Vienna in 1922 and, at 16, sent away to England when the Nazis annexed Austria. In her story, I write how she found and lost a husband, and then found another who killed her. You can read „L is for Lisbeth“ here.

At the time of writing „L is for Lisbeth“, I surmised that she came from a Jewish family, but I wasn’t sure. With the help of Sadie Nelson, a professional genealogist, I was able to track down her parents, Adelheid and Jenö Frank. This is their story.

Transport 2 left from the Aspang station in Vienna on February 19th, 1941. There were 1,010 Jews on board. Jenö Frank und his wife Adelheid (nee Popper) were on board. The train from the Deutsche Reichsbahn was headed for Kielce in Poland and was the second deportation in a series that was intended to clear Vienna of Jews, so that the Nazis could take over their property. Only 18 Jews on that train survived the Holocaust. Adelheid and Jenö were not among the survivors.

Jenö Frank was born on February 28th, 1883, in the village Hidvég-Ardó in Northern Hungary, on the border to Slovakia. The name Jenö is Hungarian and is synonomous with Eugen in German. Adelheid Popper was born on September 3rd, 1886 in Prague, Czechoslovakia. They met and married in 1914 in the Synagogue in Tempelgasse in Vienna, Austria, known as the Leopoldstädter Tempel, a beautiful building in Oriental style which served as a model for other synagogues in Zagreb, Prag, Sofia, Budapest, Kraków and Kyiv. The building was destroyed as a result of Kristallnacht, the night of 9-10 November, 1938.

1938 was also the year that the Nazis annexed Austria, and the year Adelheid and Jenö sent their daughter to England, thus saving her life.

In order to confiscate Jewish property, most Jews were forced by the Nazis to relocate and to move into overcrowded „Judenhäuser“, or to share their flat with several other families. Before Adelheid and Jenö were deported, they lived in Alser Straße 40 in Alsergrund, a district with a large Jewish population. Whether this was their original flat or they had moved there, we do not know. We do know that 6,910 Jews were deported and murdered from the district of Alsergrund. Today, we find „Steine der Erinnerung“ (memorial stones) outside of two houses in Alserstr. and many more in the district.

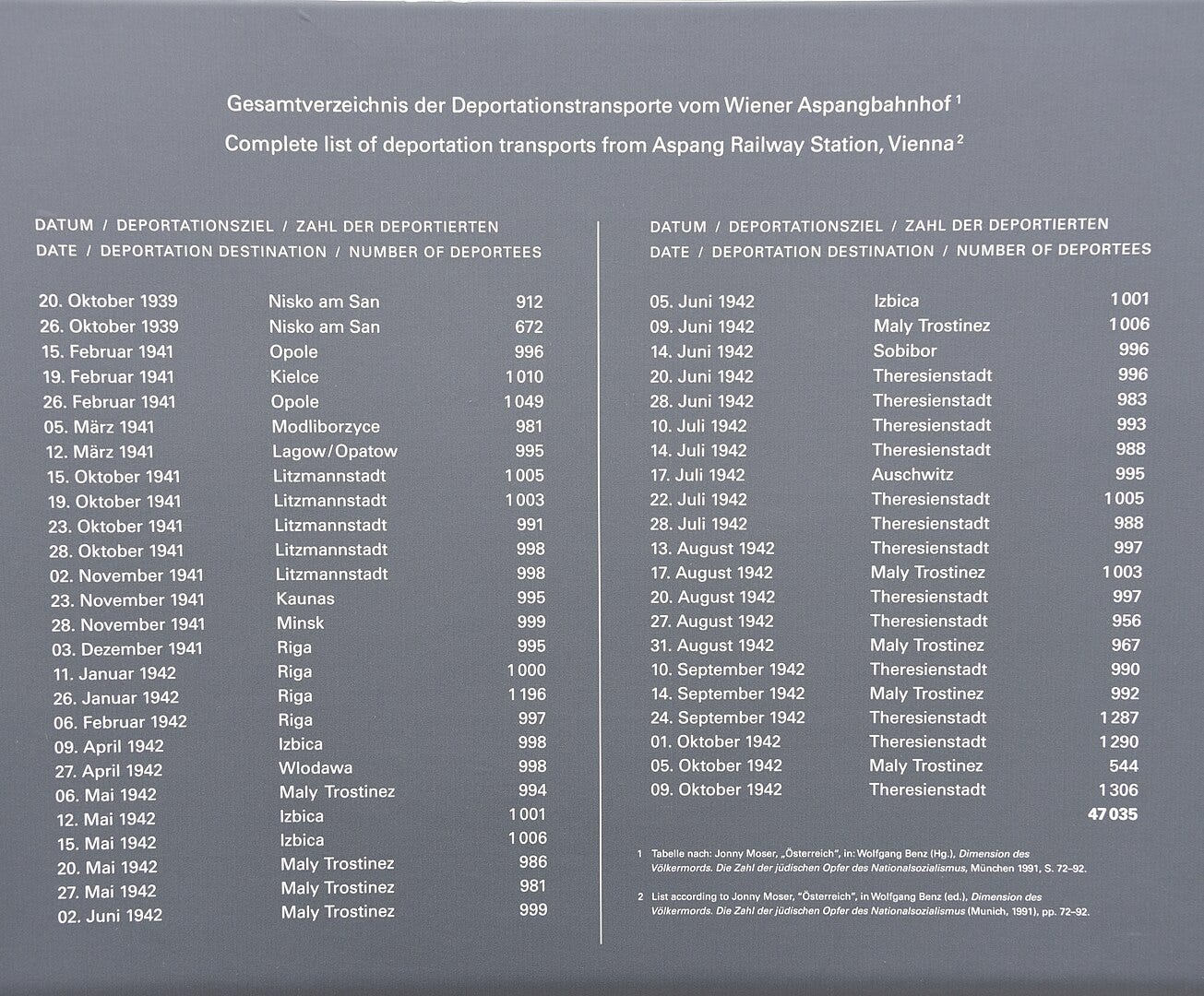

Reichsleiter Baldur von Schirach applied to Hitler for approval for a mass deportation of Jews on October 2nd, 1940, and approval was granted on December 3rd, as notified by Hans Heinrich Lammers, head of the Reichskanzlei. Altogether 47,035 Jews were deported from Aspang Railway Station, Vienna.

A few days before each transport, the Jewish Gemeinde (Community) received a list of names from the Zentralstelle für jüdische Auswanderung (Central Office for Jewish Emigration), Vienna. The community had to inform the deportees and make sure they turned up at the school building in Castellezgasse 35, from where they were taken to the station. Each person was forced to sign a document stating that they were leaving of their own free will and turning over their property to the state. It was planned meticulously.

Adolf Eichmann was responsible for the deportation, among others. The names of all 65,000 murdered Viennese Jews have been recorded on the Shoah Wall of Names in Ostarrachi Park, Vienna.

February 19th, 1941, was bitterly cold, around -12° C. It is unlikely that they knew where they were being taken or why. The distance they travelled was nearly 600 km to a place called Kielce, about 100 km north of Kraków. Many of the older and weaker deportees got sick on the way.

After Transport 2 arrived in Kielce, the deportees were first housed with local families. But the numbers were growing exponentially, because the plan was to deport all the Jews into ghettos and then to murder them. The plan was codenamed „Aktion Reinhardt“ and the deportations were the first step in the systematic murder of all Jews and Roma in Poland. Already, before the Viennese Jews even arrived, the Kielce population had grown from 18,000 to 25,400, swollen by deportations from other parts of Poland. The typhus epidemic of 1940 was one of the results of overcrowding.

A Judenrat (Jewish Council) was set up to represent the Jewish community in dealing with the Nazi authorities. Moshe Pelc led this and had the job of making all Jews wear a Star of David on their outer garments. All Jewish-owned factories, shops and other property were taken from them. Pelc did his best to get provisions supplied but in August 1940 he asked Herman Lewi to take over the leadership of the Judenrat.

Not long afterwards, on March 31st, barbed wire and high fences were put up and guards were posted. A ghetto was established by the SS and there was no way to get out. Non-Jews moved out and Jews were forced to relocate to the ghetto within one week. The ghetto gates closed on April 5th, 1941. One woman, Alice Schleifer described it in a letter:

„We've been in a closed ghetto since Saturday. I'll explain to you in a few words what it's like: excluded from the outside world, only on limited special roads that are surrounded by wire. No contact with other people. Paula, if you could see us. - It's a true picture of despair. There is already the 100th case of typhus among us…“

The deportations continued until August 1942 when there were around 27,000 Jews living in the ghetto, from Vienna, Poznan and Lódz. 4,000 died from hunger, typhus and other sicknesses caused by overcrowded living conditions. But now the real horror was to begin.

The ghetto was liquidated in August 1942. The Final Solution for Kielce began on August 20th with round-ups. Jews unable to move, sick or elderly were shot on the spot. These numbered around 1,200.

Between 20,000 and 21,000 Jews were transported from Kielce to Treblinka II, the killing camp, and murdered in gas chambers there. Under „Aktion Reinhardt“ 250,000 Jews were taken from the Warsaw Ghetto and murdered in Treblinka.

Those who were fit enough to work were spared the gas chambers for two more years and sent to work in forced labour camps, both men and women were sent to the Hasag Granatwerke (Hugo Schneider AG, arms manufacturer), or to Ludwigshütte metal factory (making bicycles or transportation), women to Henrykow (wood work). Some of these Jews tried to organise an uprising by secretly producing arms in the metal workshops. But this was foiled because the Chief of the Jewish Police, Wahan Spiegl, informed the Gestapo.

By August 24th, 1942, there were only 2,000 people left in the ghetto: skilled workers, the Judenrat and their families, and the Jewish Police. However, these were also sent to work camps in Stolarskastr. and Jasna St. On May 23rd, 1943, these people were sent to Starachowice, Skarzysko-Kamienna, Pionki or Blizyn. 23 children, some of them babies, were taken to Pakosz cemetery and shot.

By September 1943, the Soviets were making headway into Poland and the slave labour camps were abandoned. But this was not the end of the trail for those who had escaped Treblinka. These people were sent to Auschwitz or Buchenwald and murdered there.

By the time Treblinka was dismantled in the Autumn of 1943, in just over one year, 925,000 Jews had been murdered there, as well as other Poles, Roma and Soviet prisoners of war. It is highly likely, that Adelheid and Jenö were among those killed. Their names are not in the memorial book of Treblinka which only numbers about 114,000, but the project is ongoing. Adelheid and Jenö are, however, listed as being on Transport 2 to Kielce on February 19th, 1941. After that, we don’t know how they died, we only know they did die.

Afterword

Whether Lisbeth was able to get any information about what had happened to her parents is not known. But the writer of the article in the Maidenhead Advertiser on October 21, 1960, who was the only journalist who bothered to do the work of finding out about Lisbeth’s life, knew that her parents had been murdered by the Nazis. So either Lisbeth also knew and told someone else in her circle of friends, or the journalist was an excellent researcher. The only point he or she wrote about Lisbeth’s parents that I have not yet been able to verify is the claim that Adelheid was a concert pianist.

Heartfelt and harrowing, your story reminds us of those days of horror! Remembering and sharing the stories of each one of the names inscribed on ‘the wall’ is a legacy of a different kind!