K is for Killing

If you’ve been following the story of “Uncle Len, Wife-Killer” you will have gleaned the following information:

Who the main characters are: in A is for Ashworth

That the killing took place in Lisbeths house in Fairacre, Maidenhead, in B is for Berkshire, Basingstoke and Burnley, and the trial took place at the Berkshire Assizes in Reading.

What we know about what happened to the children during and after their mother was killed, in C is for Care of the Children.

About his marriage(s) to my Aunt, in D is for Dinah.

How the killing was seen legally and by the media, in F for Femicide.

Where Ashworth was most likely posted before the killing and possibly after release from prison, in G is for Germany.

About his first wife and getting married during World War 2, in I is for Irene.

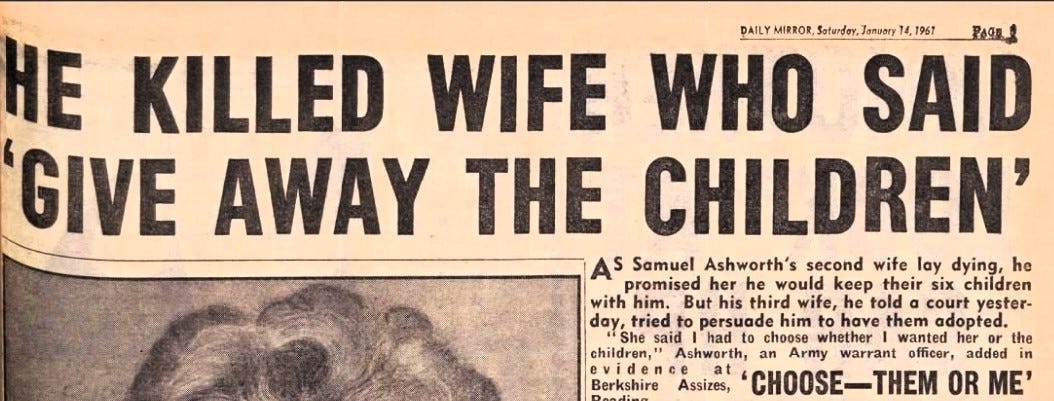

This post tries to put together what happened exactly the night of the killing. The information is severely limited due to the records of the trial being closed until 2060. We only know what was reported in the newspapers that covered the event itself in October 1960, the charging of Ashworth by the magistrates court in November 1960, and the trial itself at Berkshire Assizes in January 1961.

The killing is reported to have taken place as the result of a midnight row on October 15th 1960 between Samuel Leonard Thomas Ashworth (38), known to his later family as “Len” and his third wife Lisbeth Ashworth nee Frank (38). He probably killed her around 2am and subsequently called the police. It happened immediately following his arrival back at the house at Fairacre, Bath Road in Maidenhead, on compassionate leave.

Ashworth had applied for compassionate leave, he told the court, because his wife had written to him to say she needed to discuss the care of the children. The letter was read out in court. In the letter she said she did not feel at all well and implied that the problem could endanger their marriage. Three of the eight children were staying at Ashworth’s second wife’s mother’s house. It is unclear how long this arrangement had gone on or if there was pressure to end it. Ashworth claimed that his wife had “persuaded” him to send the children away.

The main problem seems to be that Lisbeth, according to Ashworth’s evidence, did not want to take all eight children with them to live in the Army barracks in Germany. She had put the house up for rent from November onwards, so there were only two weeks to go before the family was due to move to Germany.

Ashworth claims that his wife presented him with an ultimatum: choose her or his children, or at least some of his children. He said that she had argued that the small boys would be easiest to find homes for. They were aged 4, 3 and 1. He remembered that she said not to be sentimental about it, but he could not remember the actual killing itself, saying he “just snapped” and the next thing he knew he was “shaking her neck”.

The inquest showed that Lisbeth’s brain had been bruised by being hit over the head with a glass bottle. Ashworth admits that he had been washing up and had had a wine bottle in his hand. He had been “going back and forth from the kitchen to the sitting room”. Lisbeth was probably in the sitting room, sitting on the sofa, as that is where she was later found. The inquest found that the skull was not fractured and Lisbeth was not killed by the blow to the head, but by “asphyxiation, due to manual strangulation”. In other words, Ashworth had gone on to strangle her, after hitting her on the head with the bottle.

Now, it seems strange that Ashworth was washing out a wine bottle. This may have been a way of explaining why he had a bottle in his hand when he went from the kitchen into the living room, and attacked her in a blind rage with the thing he happened to have in his hand. His words were: “I don’t know what came over me. Something snapped. The next thing I had something in my hand. I knew I had done something horrible.” This statement contradicts the one before, that he first came to his senses to find he was strangling her. So when exactly did he realise he was in the process of killing his wife? He could not have woken up to find something in his hand at the same time as having both hands around her neck in order to strangle her.

Why did he not, after he had broken the bottle over her head, scattering glass all over the room from the force of the blow, and seeing “her face was covered in blood”, realise what he was doing and stop? Could his rage have been so uncontrollable that he then went on to strangle her, without knowing what he was doing? Possibly he had knocked her out with the blow on the head and was unaware that he was doing her to death by wringing her neck? Or was she still conscious and screaming at him, so that he was trying to make her stop?

Ashworth’s convenient lack of memory means that we cannot know what happened in those long minutes where he killed her. Because strangling someone is not a quick process, it would have taken some at least some minutes, depending on if she was conscious or not. Ashworth claims, however, that at some point he realised she was dead and tried in vain to revive her. “I tried to shake her. She would not wake up. I don’t know what happened,” Ashworth said. He also said that the baby was crying.

When the police arrived at 2:30 am, Ashworth was standing in the doorway with a child in his arms. PC Kenneth Beckingham said that Ashworth said: “I’ve stabbed my wife. I think she`s dead.” Did he say that to suggest he was confused, or was he indeed confused about what he had done and where the blood had come from? And yet the broken glass and the bottle neck would have given him a clue, unless he thought he had broken the bottle and stabbed her with the neck. Beckingham said Ashworth was in “a terrible state” and kept holding his head in his hands.

The magistrates’ court reduced the charge from murder to manslaughter, saying there was no evidence of aforethought or extreme malice.

In January 1961, the court found Ashworth guilty of manslaughter. The papers reported that he had been “cleared of murder”. The presiding judge Mr Justice Finnemore said: “I am extending mercy as far as I can. This is a more than usually distressing case but I cannot shut my heart to the fact that an inoffensive woman was done to death.” This statement is interesting, in that the judge clearly felt the need to extend mercy, suggesting that Ashworth was in some way to be pitied. Then he adds that he cannot shut his heart to Lisbeth, which implies that others would do so. The word “inoffensive” is also telling. Does it mean that what Lisbeth said or did was not offensive? Yet others, including the media, put it that her behaviour was enough to incite an attack on her person. Finnemore added that “the law of the country, as in any civilised country, seeks to preserve the sanctity of human life”.

The law of provocation seems to have played a role in this case, that is to say that the preceding events caused the defendant, who is otherwise reasonable, to lose his self-control and is therefore less morally culpable. The court obviously accepted Ashworth’s defence that his wife had said things that had incited him to kill her, like that he must choose between her and the children. The father of his second wife, Frederick Pettitt said that Ashworth was devoted to the children and “obsessed” with the idea of keeping the family together. This obsession does not seem to feature as a plausible defence of diminished responsibility, instead a picture is painted of the devoted father being provoked to a loss of self-control by a cruel woman who is threatening to have his children taken away. The fact that she could not have forced him to give up his children and that the Army had supported him in the six months that he had to stay home and look after his children, before he found Lisbeth, does not seem to feature as an argument, at least not in the media.

Provocation does not make a defendant not guilty of a crime, but is regarded as a mitigating factor. The law of provocation was outlined in the Homicide Act of 1957 and has been criticised for its discriminatory nature in instances of intimate femicide, i.e. the killing of a woman by a spouse or romantic partner. It has frequently been used to secure a manslaughter rather than a murder charge and to get the prison sentence reduced for a male killer. When a woman kills her husband, however, the court is less likely to find in her favour if she does not act immediately but, for instance, waits for her partner to fall asleep before killing him.

The fact that the two had come together through a marriage bureau advertisment in the paper would suggest that the agreement for her to look after the children while he was posted abroad was the basis of their marriage. His complaint that she didn’t love the children after such a short and obviously stressful time alone with them could have swayed the court to see her having broken the deal, but does not mean that she was cruel or had provoked Ashworth to violence by proposing what she saw as the only practical solution. Interestingly, only English law considers provocation to violence to be a crime in and of itself.

Also contradictory are the reports of how gravely distressed he was by his wife’s death. And yet he claims that only months later he fell in love and married Lisbeth. The reports of the killing, the defence Ashworth gave, and what he said publicly, are full of contradictions. In my view, the media seemed to put Lisbeth on trial, rather than Len, and public sympathy seems to have lain with the soldier, rather than the “enemy alien”.

Next up: L is for Lisbeth

So very sad that her life was cut short.